The give and the take

After leaving Bermuda, the weather worsened. Squalls whipped around us at 40 knots. High waves hit us like a speeding train, the sound and the smack waking those trying to sleep. Water drenched the helmsman. And there was a leak. We would rise on a wave in the night, the wind and the water would do their work, back down we'd see we had turned 90 degrees, from east to north in seconds and have to get back on course. Then as if it felt sorry for us it would let up and we'd glide through the water at 7 knots like there was nothing more we or the boat were made for. The sea looked beautiful but we knew it could kill and we had put a house on it. We had 1837 nautical miles to sail, 15 days, 4 hours on, 4 hours off. And in that time we got to not caring what day it was, we did the same things each shift, woke, dressed, put on lifejackets and safety lines, got on deck—to fight it was to become frustrated, instead there were benefits we felt but could little express. When our lives travelled at 5 miles an hour, time was a thing we could stay inside rather than swipe away with an impatient thumb. The wind dropped further and we lived at 2 miles an hour. We had the conversations we felt were not happening in the UK, remembered a time when we used to knock on a neighbour’s door to say hello, see if they were okay or needed something from the shop, how we used to talk to others about anything without it feeling a criminal act, expressed frustration that the media had turned into a gameshow where news shows were set up to entertain rather than explain, wondered when we arrived back in Portsmouth in July if Israel would have bombed Iran, or a skirmish occurred in the South China Sea or a civil war started in the UK. When we sat in the cockpit and peeled clementines it was like discovering them anew, taking a piece at a time to enjoy and we could forget it all. We had this time to think, to not know what the world was doing, it was just us here, we could die, we could live, go fast or slow or somewhere in that settled middle, think about how to be after this, had we wronged anyone we needed to repair relations with, who were the friends we wanted to empty bottles with, what was important in this complicated world and we'd find an answer in something as simple as a glass of clear cold water—I had looked at the sun, the moon, the stars, the sea, the birds, the day, the night, felt the wind, the heat and the cold, heard the sea heave and rush and crash, watch it still and have it throw me around, wiped my sweat, smelt my clothes, ate slowly, slept a little, worked a lot, sat with the others in silence and it seemed enough to build another life from. I could not escape death but perhaps what I had become, a new chapter could be written with a small boat and the sea, as a younger man I would tear pages from notebooks when I'd made a mistake trying to keep them perfect and a few pages later make another and have to accept I had lost, older now I knew I had not lost but learned, mistakes were important, you could erase what you had written but you could still see where you had pressed into a page with a pencil, you had made a mark, we all had a history, I could keep mine in my notebooks, my photographs and my mind and carry on. It was easy to see the sea and the wind as friends when they let us sail and enemies when they made us fail but they were both of those and all of the between. We could not give ourselves completely to them because without any remorse they could turn our boat and let us drown, neither could we take from them completely, they would give us the tide and the blow to move forwards then take them away or work against us. The times we felt all was on our side came with the times it was not. All we could do was keep going as they surrounded us, at times it felt like a fight, others an argument and then a compromise all the way to them wishing us well on our way, nothing was perfect, the rise came with the fall, the swell with the calm and the give with the take.

As we passed the halfway point it seemed there was no end of dolphins. They came in the day and the night with their young. They would head over to glide along the boat and swim ahead. We first spotted them at 34.13N, 49.45W. On the 26th of May at around 2130hrs, while on the helm, I saw a dolphin jump high across the front of the boat then swim along the port jumping three more times as high as the cabin roof, I could only imagine it was happy. At night they looked like torpedoes heading for the boat as they pressed through the water near the surface, and one day it seemed there were around fifty on either side of the boat, and again on the port side around 8 jumped in unison. On dry land, I read a paper arguing the theory that dolphins are playing is difficult to prove, what had been shown instead was they saved energy when riding the bow of a boat breathing up to 45% less than when swimming freely. They followed us into the Azores breathing easy, we arrived early in the morning, the lights of Horta sat low on the land silhouetted against the starry sky. Bem-vindo a Portugal.

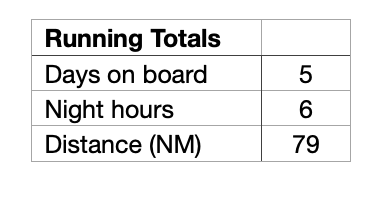

Logbook, January 2025:

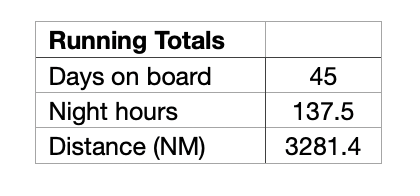

Logbook, June 2025:

Until the next time thank you for reading and please share this post with friends,

Adnan

Marina da Horta, Portugal, 2025

Adnan Sarwar is a philosophy student at the University of Oxford and a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. He won The Bodley Head/Financial Times essay prize, edited for The Economist and is an Iraq war veteran of the British Army.

References

Fiori, L. et al (2024), Energetic savings of bow-riding dolphins. [Online] Nature. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-81920-y , Accessed 31 May 2025